Published: Jun 26, 2017 by Javier Fuentes

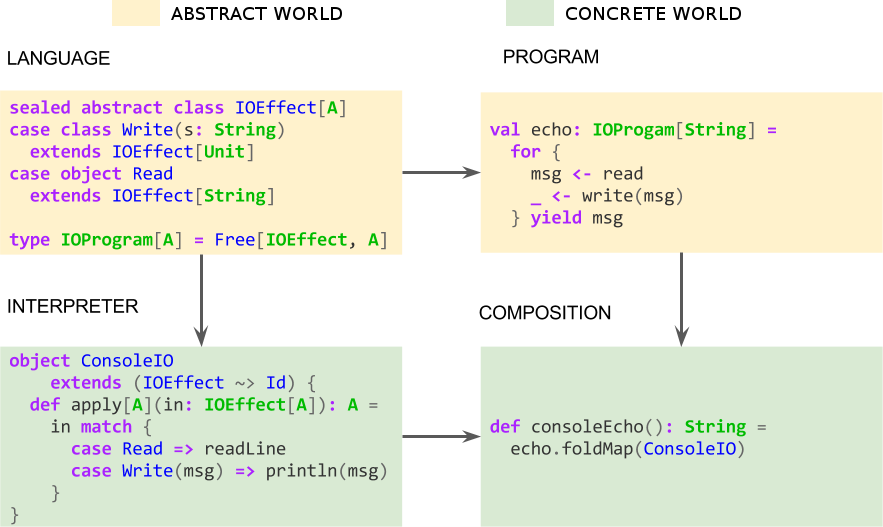

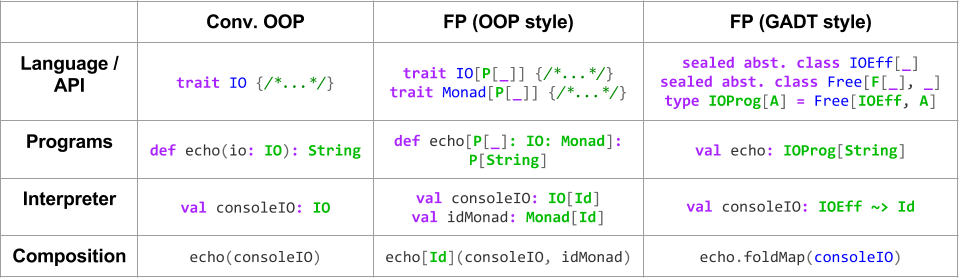

In the series of posts about the essence of functional programming, we’ve already seen how we can build purely declarative programs using GADTs. This is a picture of what we got (using more standard cats/scalaz data types):

This program above has several advantages over an impure one, given that it completely separates the business logic (the WHAT) from the interpretation (the HOW). This gives us full room of possibilities, since we can change the whole deployment infrastructure without having to change the logic in any way. In other words, business logic changes affect only business logic code and infrastructure changes affect only interpreters (provided that neither of these changes affect the DSL, of course). Some changes of interpretation could be, for instance, running the program using Futures in an asynchronous way, or running it as a pure state transformation for testing purposes using State.

Now, you might be wondering, is OOP capable of achieving this level of declarativeness? In this post, we will see that we can indeed do purely functional programming in a purely object-oriented style. However, in order to do so, the conventional techniques that we normally employ when doing OOP (plain abstract interfaces) won’t suffice. What we actually need are more powerful techniques for building Functional APIs, namely type classes!

The issues of conventional OOP

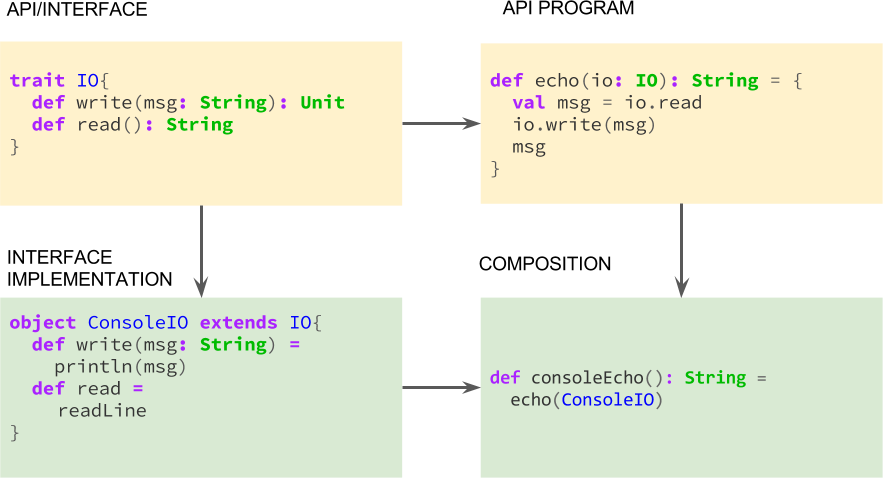

In OOP, the most common way to achieve declarativeness is by using plain abstract interfaces, of course. In a similar way to the GADT approach, we can acknowledge four parts of this design pattern:

- Interface/API

- Method/Program over that interface

- Concrete instances

- Composition

Here there is a very illustrative diagram of this approach:

However, this is just one step towards declarativeness; it separates a little bit WHAT and HOW, since IO is an abstract interface, but we still have a very limited range of possible HOWs. This is quite easy to prove just by giving a couple of interpretations we can not implement. These are, for instance, asynchronous and pure state transformations. In the former case, we can’t simply implement the IO signature in an asynchronous way, since this signature forces us to return plain values, i.e. a value of type String in the read case, and a value of type Unit in the write case. If we attempt to implement this API in an asynchronous way, we will eventually get a Future[String] value, and we will have to convert this promise to a plain String by blocking the thread and waiting for the asynchronous computation to complete, thus rendering the interpretation absolutely synchronous.

object asyncInstance extends IO {

def write(msg: String): Unit =

Await.result(/* My future computation */, 2 seconds)

def read: String = /* Idem */

}

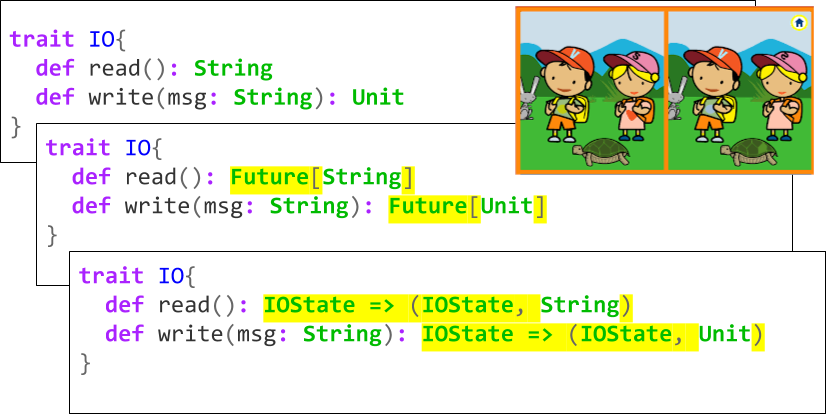

Similarly, an state-based interpretation won’t be possible. In sum, if we want an asynchronous or a pure state transformer behaviour for our programs, we would have to change the original interface to reflect those changes and come up with two new APIs:

trait IO { // Async

def write(msg: String): Future[Unit]

def read(): Future[String]

}

trait IO { // Pure state transformations

def write(msg: String): IOState => (IOState, Unit)

def read(): IOState => (IOState, String)

}

This is clearly not desirable, since these changes in API will force us to rewrite all of our business logic that rests upon the original IO API. Let’s go ahead and start improving our OOP interfaces towards true declarativeness. As we’ve seen in this pattern, we can distinguish between the abstract world (interface and interface-dependent method) and the concrete world (interface instance and composition).

Abstract world: towards Functional APIs

We may notice that there are not many differences among the three interfaces we’ve shown so far. In fact, the only differences are related to the return type embelishment in each case:

We can factor out these differences and generalize a common solution for all of them; we just need to write our interface in such a way that the instructions (methods) don’t return a plain value, but a value wrapped in a generic type constructor, the so-called embelishment; from now on we will also call those embelishments programs, as they can be considered computations that will eventually return a result value (once the asynchronous computation completes, or when we enact the state transformation).

trait IO[P[_]] {

def read: P[String]

def write(msg: String): P[Unit]

}

// Console

type Id[A] = A

type SynchIO = IO[Id]

// Async

type AsyncIO = IO[Future]

// Pure state transformations

type State[A] = IOState => (IOState, A)

type StateIO = IO[State]

Wow! our new interface is a generic interface, and, more specifically, a type class that solves our declarativeness problem: we can now create interpreters (instances) for both asynchronous and state transformers computations, and for any other program you may think of.

We call this type of class-based APIs functional APIs, due to their ability to totally decouple business logic from interpretation. With our traditional interfaces we still had our business logic contaminated with HOW concepts, specifically with the limitation of running always in Id[_]. Now, we are truly free.

Abstract world: programs

Ain’t it easy? Let’s see what we have so far. We have a type class that models IO languages. Those languages consists on two instructions read and write that returns plain abstract programs. What can we do with this type class already?

def hello[P[_]](IO: IO[P]): P[Unit] =

IO.write("Hello, world!")

def sayWhat[P[_]](IO: IO[P]): P[String] =

IO.read

Not very impressive, we don’t have any problem to build simple programs, what about composition?

def helloSayWhat[P[_]](IO: IO[P]): P[String] = {

IO.write("Hello, say something:")

IO.read()

} // This doesn't work as expected

Houston, we have a problem! The program above just reads the input but it’s not writing anything, the first instruction is just a pure statement in the middle of our program, hence it’s doing nothing. We are missing some mechanism to combine our programs in an imperative way. Luckily for us, that’s exactly what monads do, in fact monads are just another Functional API: :)

trait Monad[P[_]] {

def flatMap[A, B](pa: P[A])(f: A => P[B]): P[B]

def pure[A](a: A): P[A]

}

Well, you won’t believe it but we can already define every single program we had in our previous post. Emphasis in the word define, as we can just do that: define *or declare* in a pure way all of our programs; but we’re still in the abstract world, in our safe space, where everything is wonderful, modular and comfy.

def helloSayWhat[P[_]](M: Monad[P], IO: IO[P]): P[String] =

M.flatMap(IO.write("Hello, say something:")){ _ =>

IO.read

}

def echo[P[_]](M: Monad[P], IO: IO[P]): P[Unit] =

M.flatMap(IO.read){ msg =>

IO.write(msg)

}

def echo2[P[_]](M: Monad[P], IO: IO[P]): P[String] =

M.flatMap(IO.read){ msg =>

M.flatMap(IO.write(msg)){ _ =>

M.pure(msg)

}

}

Ok, the previous code is pretty modular but isn’t very sweet. But with a little help from our friends (namely, context bounds, for-comprehensions, helper methods and infix operators), we can get closer to the syntactic niceties of the non-declarative implementation:

def helloSayWhat[P[_]: Monad: IO]: P[String] =

write("Hello, say something:") >>

read

def echo[P[_]: Monad: IO]: P[Unit] =

read >>= write[P]

def echo2[P[_]: Monad: IO]: P[String] = for {

msg <- read

_ <- write(msg)

} yield msg

You can get the details of this transformation in the accompanying gist of this post.

Concrete world: instances and composition

As we said, these are just pure program definitions, free of interpretation. Time to go to real world! Luckily for us, interpreters of these programs are just instances of our type class. Moreover, our console interpreter will look almost the same as in the OOP version, we just need to specify the type of our programs to be Id[_] (in the OOP approach this was set implicitly):

// Remember, `Id[A]` is just the same as `A`

implicit object ioTerminal extends IO[Id] {

def print(msg: String) = println(msg)

def read() = readLine

}

implicit object idMonad extends Monad[Id] {

def flatMap[A, B](pa: Id[A])(f: A => Id[B]): Id[B] = f(pa)

def pure[A](a: A): Id[A] = a

}

def helloConsole(): Unit = hello[Id](ioTerminal)

def sayWhatConsole(): String = sayWhat(ioTerminal)

def helloSayWhatConsole() = helloSayWhat(idMonad, ioTerminal)

def echoConsole() = echo[Id]

def echo2Console() = echo2[Id]

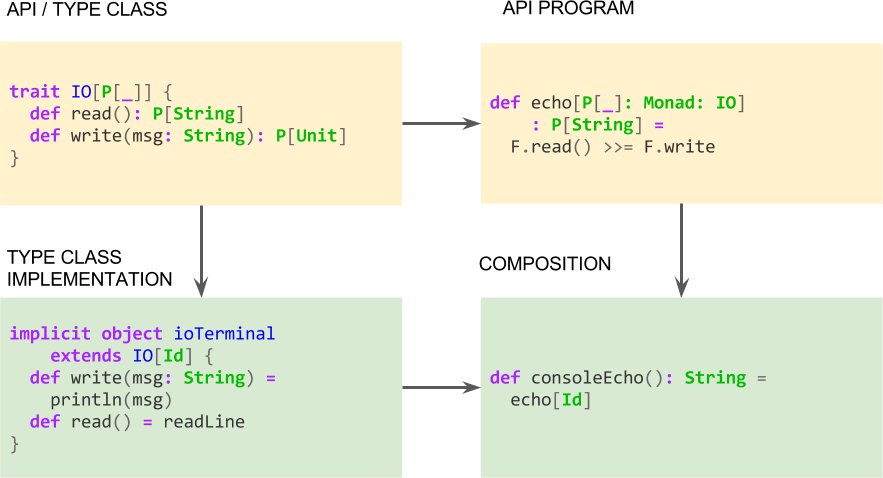

So now, we can start talking about the type class design pattern. In the same way we did with the plan abstract interface design pattern, here it is the diagram of this methodology:

Conventional OOP vs. FP (OO Style) vs. FP (GADT style)

Fine, we’ve seen two ways of defining pure, declarative programs (GADTs and Functional APIs), and another one that unsuccessfully aims to do so (plain OOP abstract interfaces), what are the differences? which one is better? Well, let’s answer the first question for now using the following table:

As you can see, the GADT style for doing functional programming (FP) favours data types (IOEffect and Free), whereas FP in a OO style favours APIs (IO and Monad); declarative functions in the GADT style return programs written in our DSL (IOProgram), whereas declarative functions in FP (OO Style) are ad-hoc polymorphic functions; concerning interpretations, natural transformations used in the GADT style correspond simply to instances of APIs in OO-based FP; last, running our programs in the GADT style using a given interpreter, just means plain old dependency injection in FP OO. As for the conventional OOP approach, you can just see how it can be considered an instance of FP OO for the Id interpretation.

About the question of which alternative is better, GADTs or Functional APIs, there’s not an easy answer, but we can give some tips:

Pros Functional APIs:

- Cleaner: This approach implies much less boilerplate.

- Simpler: It’s easier to perform and it should be pretty familiar to any OOP programmer (no need to talk about GADTs or natural transformations).

- Performance: We don’t have to create lots of intermediate objects like the ADT version does.

- Flexible: We can go from Functional APIs to GADTs at any time, just giving an instance of the type class for the ADT-based program (e.g.,

object toADT extends IO[IOProgram]]).

Pros GADTs:

- More control: In general, ADTs allows for more control over our programs, due to the fact that we have the program represented as a value that we can inspect, modify, refactor, etc.

- Reification: if you need somehow to pass around your programs, or read programs from a file, then you need to represent programs as values, and for that purpose ADTs come in very handy.

- Modular interpreters: Arguably, we can write interpreters in a more modular fashion when working with GADTs, as, for instance, with the

<a href="https://github.com/atnos-org/eff">Eff</a>monad.

Conclusion & next steps

We have seen how we can do purely functional programming in an object-oriented fashion using so-called functional APIs, i.e. using type classes instead of plain abstract interfaces. This little change allowed us to widen the type of interpretations that our OO APIs can handle, and write programs in a purely declarative fashion. And, significantly, all of this was achieved while working in the realm of object-oriented programming! So, this style of doing FP, which is also known as MTL, tagless final and related to object-algebras, is more closely aligned with OO programmers, and don’t require knowledge of alien abstractions to the OO world such as GADTs and natural transformations. But we just scratched the surface, as this is a very large subject to tackle in one post. Some of the topics we may see in the future are:

- Modular interpreters: How to seamlessly compose interpreters using Functional APIs is another large issue which is currently under investigation. A recent library that aims at this goal is mainecoon.

- Church encodings: In the GADT approach, declarative functions return programs that will eventually be interpreted, but with Functional APIs, we don’t see any such program value. In our next posts, we will see how the Church encoding allows us to reconcile this two different ways of doing FP.

Last, let us recommend you this presentation where we talk about the issues of this post! All roads lead … to lambda world. Also, you can find the code of this post here.

See ya!